Amazon Fantasy: The Digital Highway That Runs Both Ways

Table of Contents

How a well-intentioned plan to modernize Bangladesh's exports could pave the way for economic disruption—lessons from India's cautionary tale

The Promise

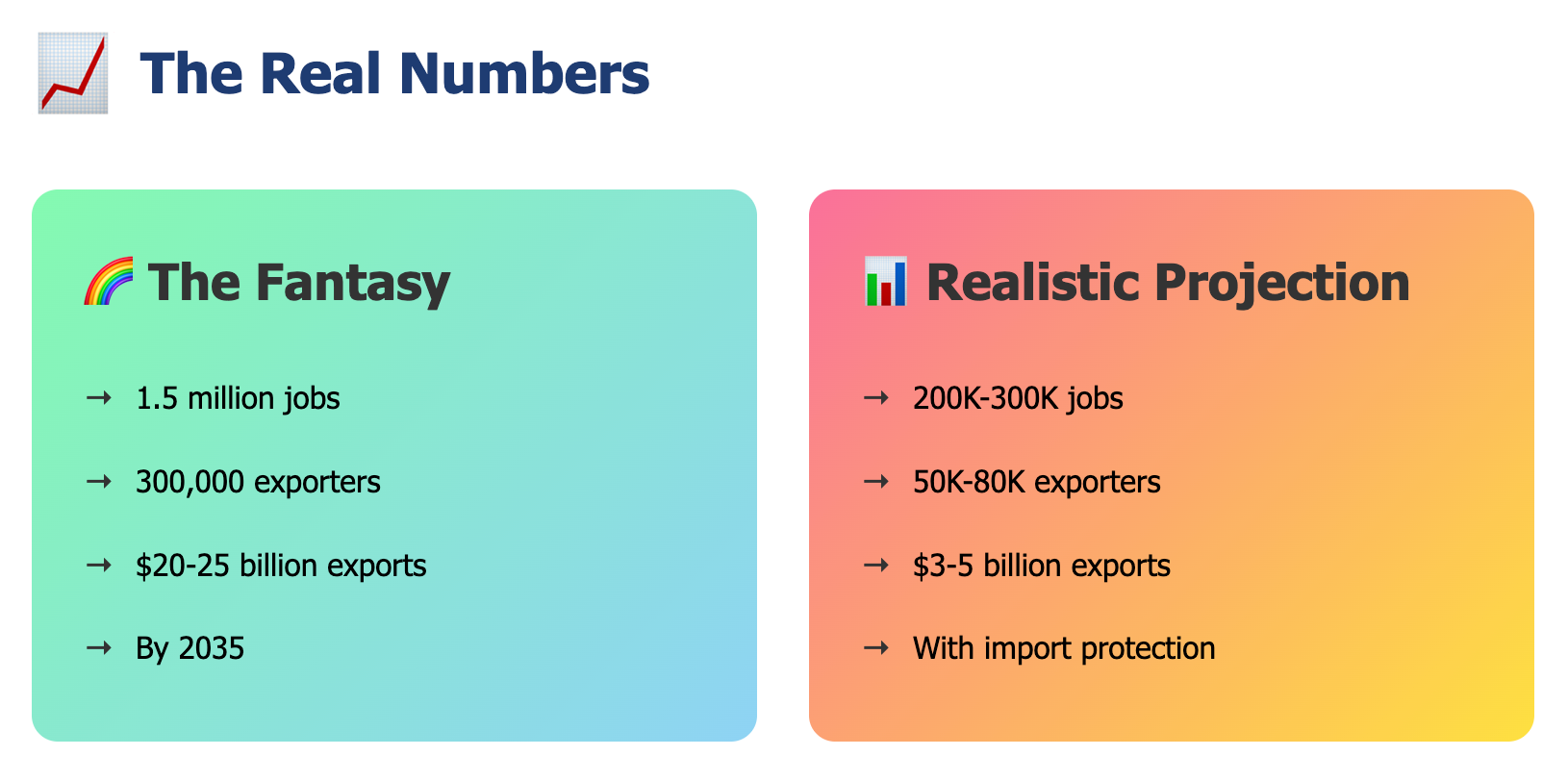

In November 2025, a policy document landed on the desks of Bangladesh's future economic planners with the force of a manifesto. Titled "The Bangladesh Amazon Economy," it promised nothing less than economic transformation: 1.5 million new jobs, 300,000 micro-exporters, and $20-25 billion in non-garment exports by 2035. The blueprint was elegant in its simplicity—upgrade customs clearance from 7-10 days to hours, automate banking payments to release funds within 48 hours, and transform nearly 10,000 post offices into export counters.

The hero of this story was Nusrat, a fictional woodworker in Bogura who would list a $50 stool online, drop it at her local post office in the morning, watch it clear customs by afternoon, and see payment in her bank account within two days. From rural Bangladesh to Boston. District to world. The honest path, finally made fast.

It sounded perfect. Perhaps too perfect.

The Indian Mirror

To understand why Bangladesh should pause before racing down this digital highway, you must first understand what happened 1,400 kilometers northwest, in India.

In 2015, Amazon launched "Global Selling" in India with remarkably similar promises. The platform would democratize exports, they said. Small artisans would bypass middlemen. Manufacturing clusters in places like Moradabad and Ludhiana would finally access global markets directly.

Ten years later, the numbers tell a story—but not the one that was promised.

Yes, India achieved $20 billion in cumulative e-commerce exports through Amazon. Over 200 cities now have sellers on the platform. Success stories abound of entrepreneurs shipping handicrafts to America from tier-three towns.

But here's what the promotional materials don't mention: India's trade deficit with China has ballooned toward $100 billion annually. In July 2025 alone, India imported $10.9 billion worth of Chinese goods. The Confederation of All India Traders reports that tens of thousands of small shops have been forced to shut down. Kirana stores—the backbone of Indian retail—have lost 25-30% of their revenue since 2018.

The digital highway runs both ways.

The Mathematics of False Hope

Let's examine Bangladesh's job creation projections with the cold eye of arithmetic.

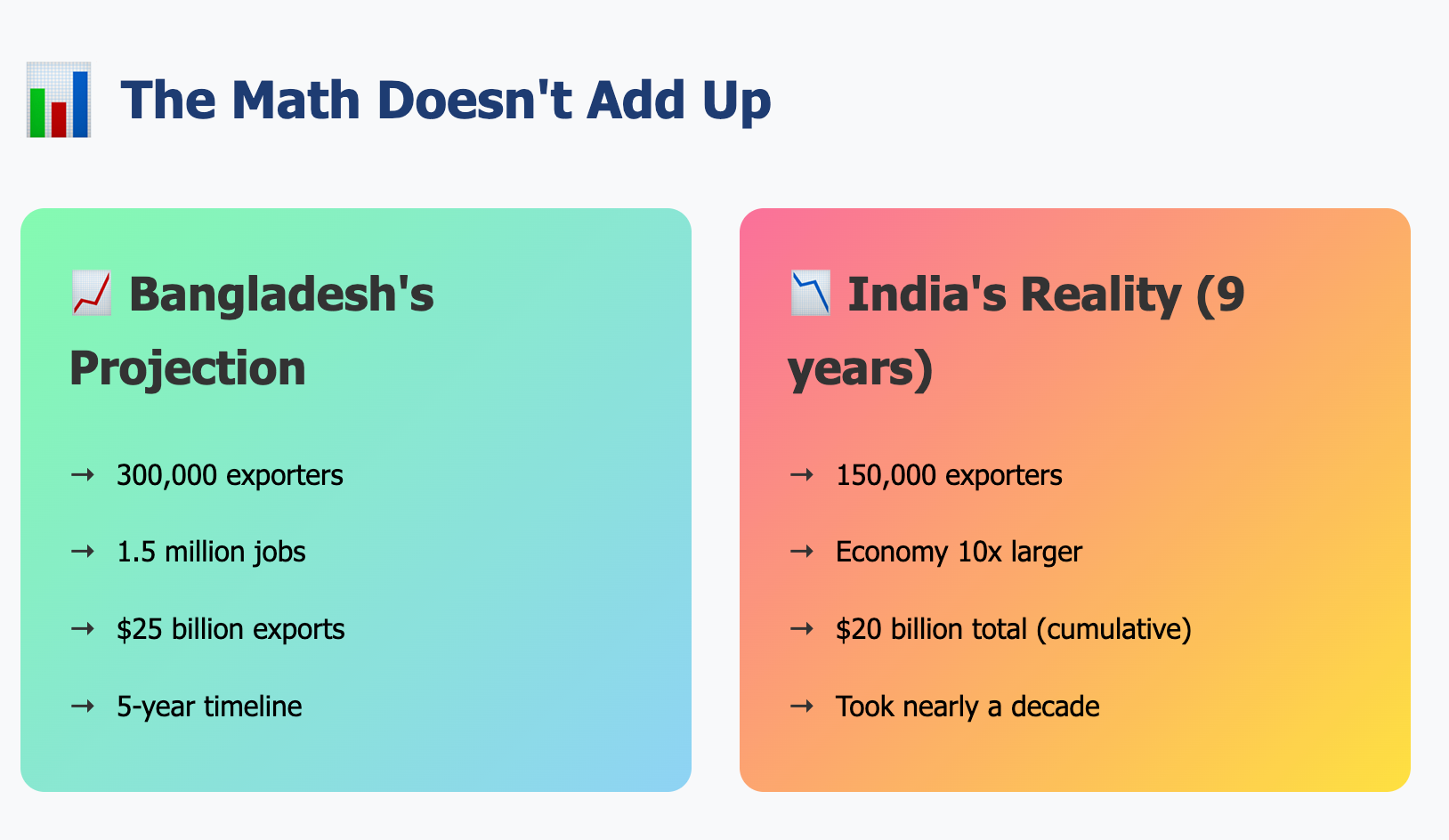

The Bangladesh proposal claims 1.5 million jobs and 300,000 micro-exporters within five years. India's comparable program, operating for over nine years in an economy ten times Bangladesh's size, has created approximately 150,000 active exporters.

Apply population proportionality: Bangladesh (165 million people) should realistically generate 15,000-20,000 exporters, not 300,000. Even if each employs three people, that's 45,000-60,000 jobs—not 1.5 million.

The document confuses self-employment with job creation. One person selling online doesn't reduce unemployment; it creates what economists call "survivorship bias"—we count the visible successes while the invisible failures disappear from statistics.

The Chinese Algorithm

Here's what the Bangladesh blueprint doesn't tell you: approximately 70-71% of products sold on Amazon globally are manufactured in China. This isn't incidental. It's structural.

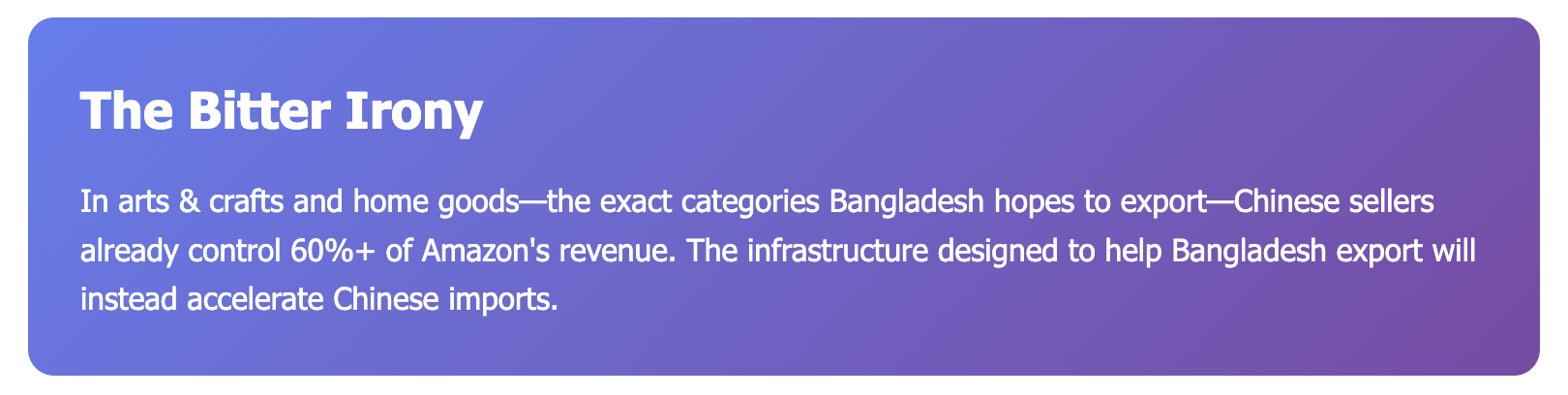

Chinese sellers don't just compete on Amazon—they dominate it. In the exact categories Bangladesh hopes to export—arts and crafts, home goods, jute products—Chinese sellers account for more than 60% of revenue.

How do they do it? Three advantages create an insurmountable moat:

First, scale. A Chinese factory can produce 10,000 units at $3 each. A Bangladeshi workshop can produce 100 units at $8 each. Amazon's algorithm favors volume, reviews, and Prime eligibility—all of which require scale.

Second, sophistication. Chinese sellers have mastered Amazon's black arts: manipulating search rankings, buying fake five-star reviews at ₹10-20 per review, using VPNs and shell companies to appear as local sellers. They've turned platform gaming into industrial policy.

Third, the infrastructure itself. The very reforms Bangladesh proposes—fast customs clearance, bonded warehouses, express courier licenses—are precisely what Chinese exporters will exploit to flood Bangladesh's market with cheap goods.

Remember Nusrat's $50 wooden stool? A Chinese manufacturer can produce a similar item for $12, ship it through the same "Bangladesh Digital Export Highway," and sell it in Dhaka for $25—undercutting Nusrat in her own neighborhood.

The Moradabad Tragedy

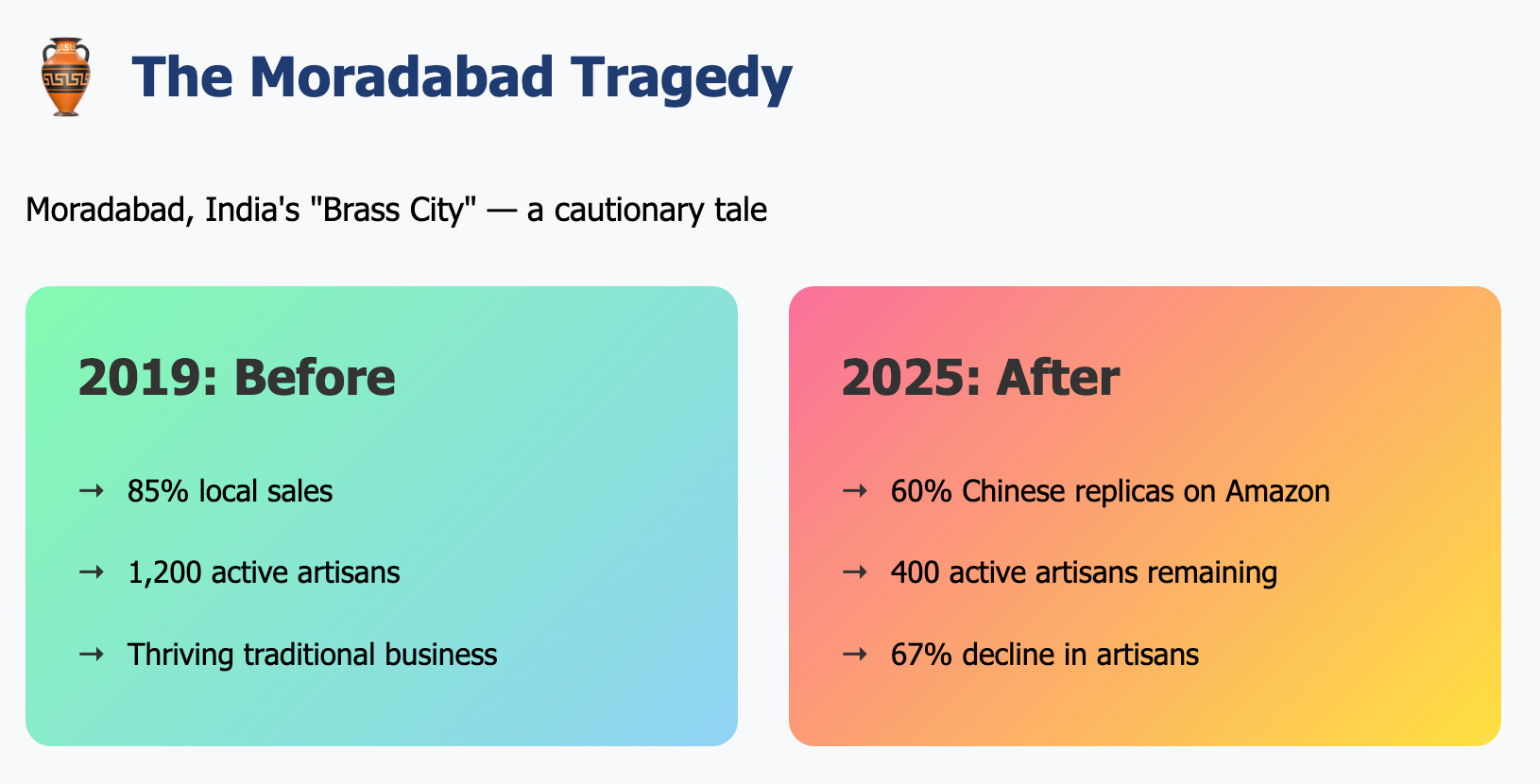

To understand what this looks like in practice, visit Moradabad, India's "Peetal Nagri"—the brass city.

In 2019, 85% of Moradabad's brassware sold locally or through traditional business-to-business channels. Local artisans numbered around 1,200 active sellers.

By 2025, 60% of Amazon's "brass décor" listings are Chinese replicas. The number of active Moradabad artisans has fallen to 400.

What happened? The same digital highway that was supposed to carry Moradabad brass to global markets instead carried cheaper Chinese brass into Indian living rooms. The infrastructure worked exactly as designed—it was just faster and cheaper for imports than exports.

Small Indian businesses report a cruel irony: Amazon's "I Have Space" program, which recruits kirana shops as last-mile delivery points, has transformed independent retailers into low-margin logistics nodes for the very platform destroying their core business.

One Kashmir businessman listed dry fruits on Amazon and didn't receive a single order for months—despite a pandemic lockdown driving e-commerce to record highs. Meanwhile, Chinese-origin dry fruits sold briskly on the same platform.

The Product-Market Mismatch

Bangladesh's comparative advantages lie in precisely the wrong categories for Amazon success:

Agricultural products: Require FDA registration, HACCP certification, temperature-controlled shipping, 90-day minimum shelf life, and extensive traceable labeling. A small Bangladeshi mango producer cannot afford a $20,000 HACCP certification for a $500 export order.

Jute products: Low-margin commodities ($2-5 per bag) competing against Chinese manufacturers who can undercut on price at any volume.

Handicrafts: Already dominated by Chinese sellers (60%+ market share) with sophisticated supply chains, professional photography, and thousands of purchased five-star reviews.

Leather goods: Face environmental compliance issues and compete against established Indian and Chinese production at higher quality and lower cost.

The document promises that faster logistics will overcome these structural disadvantages. It's like promising that a faster road will make a bicycle competitive with a motorcycle.

The 12 Percent Problem

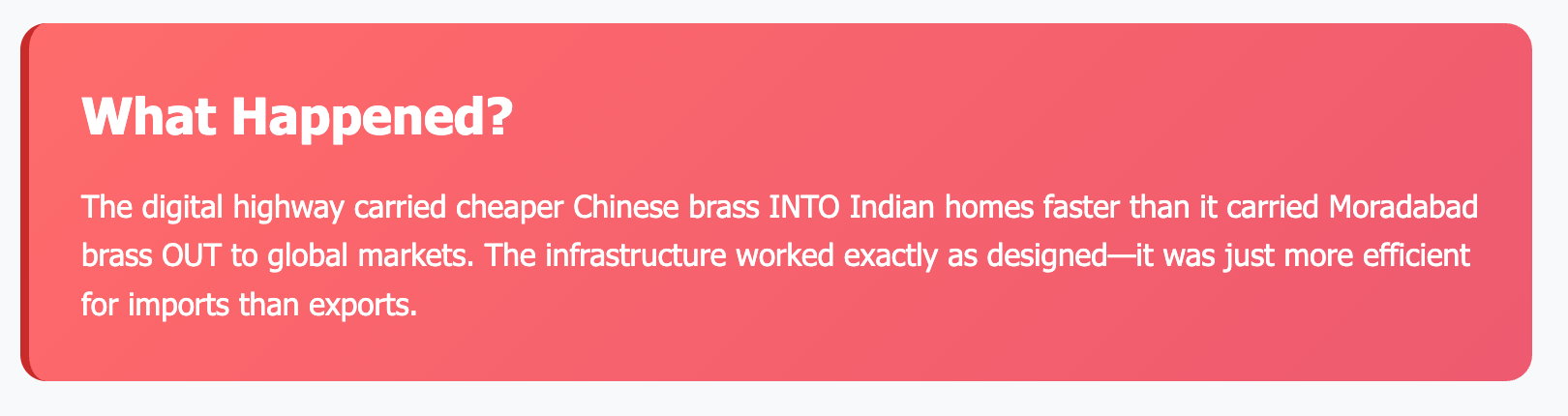

Here's the number that should terrify Bangladesh policymakers: Only 12% of Indian Amazon sellers are profitable, according to a 2024 study by IIM Bangalore.

Think about that. Nine out of ten sellers lose money. They pay 15-20% commission, storage fees, advertising costs to appear in search results, and return shipping for the 30-40% of items that come back.

The ones who survive? They're not the artisans and craftspeople the program was designed to help. They're sophisticated operators who've learned to game the system, often selling Chinese-sourced products with higher margins.

The dream was cottage industries going global. The reality is arbitrage players dropshipping Chinese goods.

What India Learned Too Late

In 2025, India's Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal accused Amazon of "predatory pricing," stating that the company's billions in investment were actually to cover business losses—not to build Indian capacity. He warned that India's traditional markets could shift entirely online within a decade, posing an existential risk to tens of millions of small businesses.

The Competition Commission of India found that 33 large retailers accounted for two-thirds of all sales on Amazon India's platform, contradicting Amazon's claims of running an equal-opportunity marketplace. Internal documents revealed the company gave discounted fees to select sellers and helped them cut special deals—creating a two-tier system where well-connected players prospered while ordinary sellers remained invisible in search results.

More than 30 Indian retailer and farmer organizations urged the government to reject Amazon's proposals to relax investment rules, citing fears of predatory pricing and unfair advantages. The Indian government now prohibits 100% foreign direct investment in inventory-based e-commerce—allowing it only in the marketplace model—specifically to prevent Amazon from crushing domestic businesses.

These weren't theoretical concerns debated in academic papers. They were emergency regulatory responses to actual devastation happening in real time.

The Efficiency Trap

Here's the paradox at the heart of Bangladesh's proposal: The better the infrastructure works, the more dangerous it becomes.

The four pillars—BECCS (customs fast lane), BD-EDPMS (automated payments), BDEFC (post office counters), and CBEOL (express courier licenses)—are genuinely excellent reforms. Reducing customs clearance from 7-10 days to hours is unambiguously good. Automating banking payments to release funds within 48 hours solves a real problem.

But infrastructure is direction-agnostic. A highway doesn't care which way the trucks drive.

The same customs fast lane that clears Nusrat's stool in hours will clear Chinese imports in hours. The same bonded warehouse that stores Bangladeshi inventory for quick dispatch can store Chinese inventory for quick dispatch. The same express courier licenses that enable direct flights to Boston enable direct flights from Shenzhen.

Bangladesh is building what amounts to a perfectly efficient two-way valve—and then expressing surprise that liquid flows toward the pressure gradient, not against it.

The Alternative Nobody Wants to Hear

There is a path forward, but it requires abandoning the seductive simplicity of the "Amazon Economy" narrative.

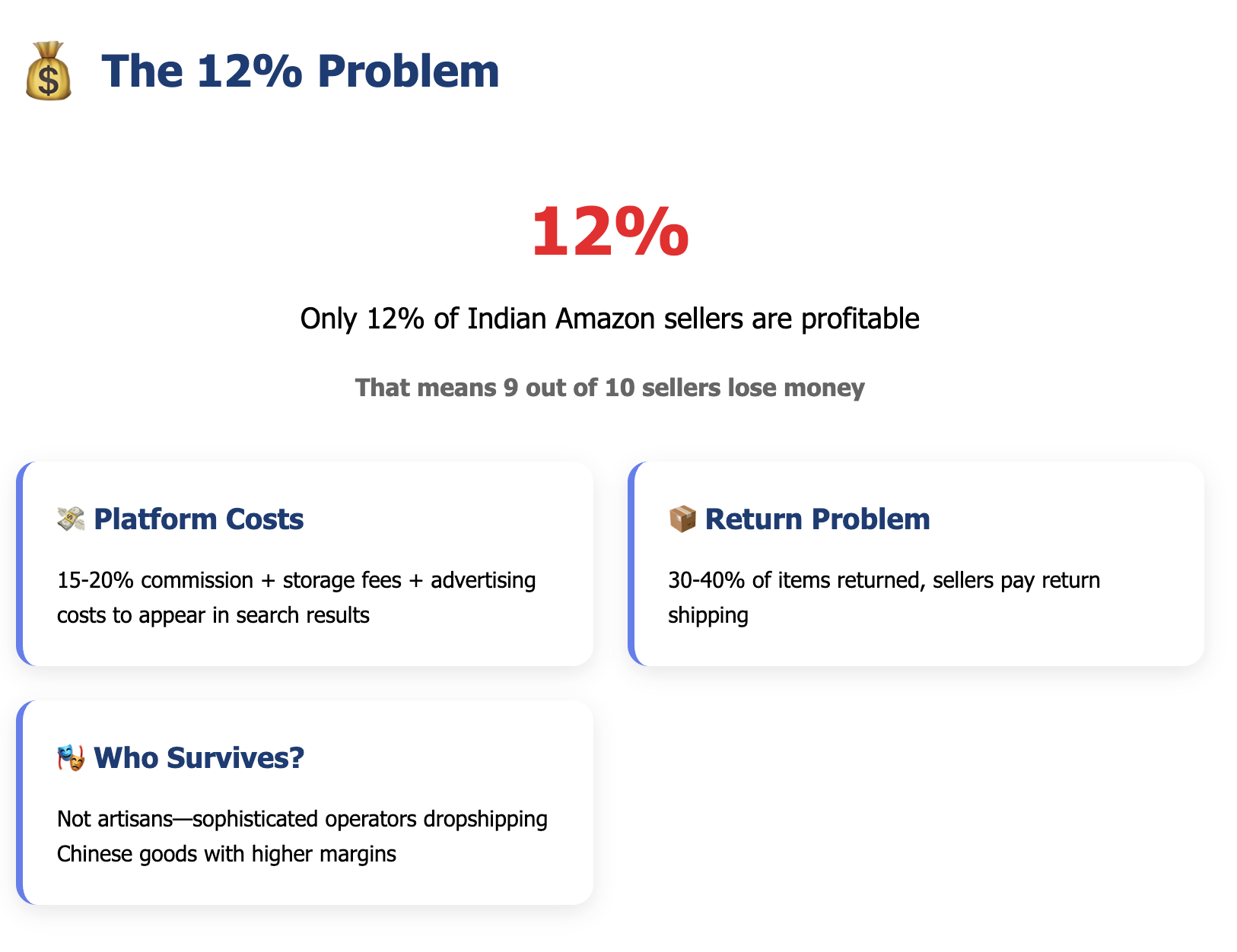

First: Implement the infrastructure reforms (BECCS, BD-EDPMS, BDEFC, CBEOL) but treat them as public utilities, not proprietary Amazon channels. India's ONDC (Open Network for Digital Commerce) offers a model—open protocols that any platform can use, preventing monopolistic capture and keeping data sovereignty domestic.

Second: Focus export promotion on business-to-business trade, not direct-to-consumer platforms. B2B relationships in specialized sectors (pharmaceuticals, leather footwear, specific garments) build industrial capacity that resists commoditization. The Bangladesh pharmaceutical sector exports $500 million annually by competing on regulated quality, not Amazon search rankings.

Third: Mandate strict quality and standards compliance as a prerequisite for the Digital Exporter ID. Don't just facilitate exports—curate them. Ensure that only producers meeting international standards can access the fast lane. This protects compliant Bangladeshi MSMEs from being undercut domestically by non-compliant imports.

Fourth: Establish an Import Monitoring & Protection Task Force with a mandate to use the same BECCS data to flag and audit large volumes of low-value, mass-market imports that directly compete with protected sectors. India's anti-dumping investigations came too late—after the damage was done.

Fifth: Prohibit 100% foreign direct investment in inventory-based e-commerce, following India's model. Allow only the marketplace model, with transparent rules against seller preferencing and mandatory fee disclosure.

This approach is harder to sell politically. It doesn't have a hero narrative. There's no heartwarming story of Nusrat shipping a stool to Boston. It's technocratic, defensive, and complicated.

But it's what the evidence demands.

The Real Number

Here's the projection Bangladesh should actually plan for:

- Realistic Phase 1 (36 months): 50,000-80,000 micro-exporters, creating 200,000-300,000 jobs (direct and indirect)

- By 2035: $3-5 billion in additional non-RMG exports, if quality control is prioritized and the import flood is actively managed

- Net employment impact: Potentially negative in the first five years if small retailers lose business faster than exporters gain it

These are still meaningful achievements. A quarter-million jobs and several billion in exports would represent genuine progress. But they're an order of magnitude smaller than the 1.5 million jobs and $20-25 billion in exports the original document promises.

The difference between these projections isn't just academic. It's the difference between manageable adjustment and economic disruption. It's the difference between farmers losing money on Amazon fees and farmers staying solvent. It's the difference between furniture workshops in Bogura competing with Chinese imports and furniture workshops closing down.

The Question

In 1492, Christopher Columbus promised Ferdinand and Isabella a western route to the spices of India. He was wrong about the destination but stumbled onto a continent. Sometimes the fantasy delivers something valuable, just not what was promised.

The Bangladesh Amazon Economy blueprint might deliver value—but as a catalyst for internal bureaucratic reform, not as a job-creation engine or export accelerator. The real win would be forcing the Bangladesh Customs Service, Bangladesh Bank, and the postal system to finally digitize and coordinate—changes that bureaucratic inertia has resisted for decades.

If that's the goal, fine. But don't sell it to 170 million Bangladeshis as an employment miracle when the more likely outcome is an import nightmare.

The Indian experience should haunt every line of the Bangladesh proposal. Not because Indians did it wrong, but because they did it exactly right—and it still didn't work the way the consultants' PowerPoints promised.

Sometimes the honest path isn't the fast path. Sometimes the gate that swings open for you swings open for everyone else too. And sometimes the digital highway you build to carry your goods to the world instead carries the world's cheapest goods to your doorstep.

Bangladesh can still modernize its export infrastructure. It can still join the digital economy. It can still diversify beyond garments.

But it cannot do so by pretending that infrastructure is strategy, that efficiency equals success, or that platforms are partners rather than extraction machines optimized for their own profit.

The Amazon fantasy promises a shortcut. What Bangladesh actually needs is a very long, very careful walk—building industrial capacity, enforcing quality standards, protecting nascent industries, and yes, improving logistics and payments, but as tools for a broader industrial policy, not as substitutes for one.

Malcolm Gladwell often writes about the dangerous seduction of the obvious explanation. Here is Bangladesh's obvious explanation: Infrastructure is broken, Amazon offers access to global markets, therefore fixing infrastructure plus Amazon equals prosperity.

The non-obvious truth is harder and sadder: Infrastructure is necessary but not sufficient. Amazon offers access but extracts rent and data in return. And prosperity for small economies in the platform age requires active defense against predatory competition, not just passive access to global logistics.

Nusrat's stool might make it to Boston. But will there be anyone left in Bogura making stools when cheap Chinese furniture floods the local market at half the price? That's the question the blueprint doesn't ask.

And that's why the Amazon fantasy remains just that—a fantasy.

The Bangladesh Amazon Economy blueprint projects 1.5 million jobs and $20-25 billion in exports by 2035. Based on the Indian comparative experience and product-market analysis, realistic projections are 200,000-300,000 jobs and $3-5 billion in exports—contingent on simultaneous import protection policies that the original document does not propose.